Trusted insiders are potential, current or former employees or contractors who have legitimate access to information, techniques, technology, assets or premises. Trusted insiders can intentionally or unknowingly assist external parties in conducting activities against the organisation or can commit malicious acts of self-interest. Such action by a trusted insider can undermine or severely impact the availability, integrity, reliability or confidentiality of those assets captured as critical infrastructure assets.

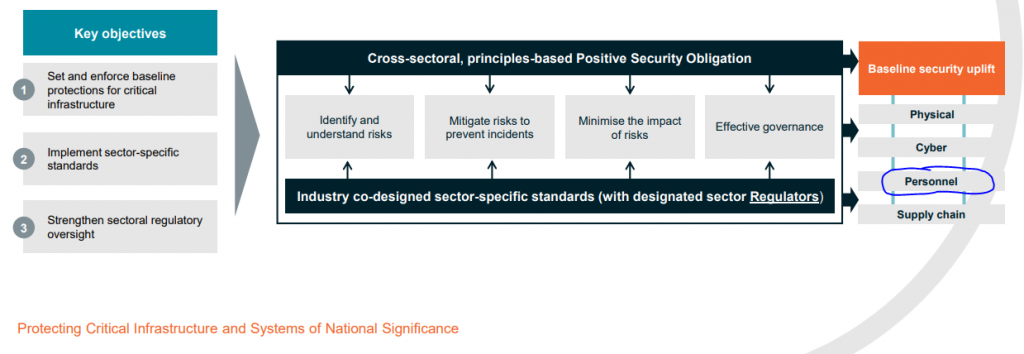

In this article, we highlight the recognition of the importance that personnel security has and industry’s understanding and ability to manage its personnel security risks through background checking systems and standards.

Background checks of individuals under the critical infrastructure risk management program will be made by ‘rules’ and AusCheck has been provisioned as essentially the default scheme to be used if the program requires it. However, Bill Page 8. Para 19 notes that a ‘background check has the same meaning as in the AusCheck Act 2007’. We feel that this is too limiting and not reflective of the public submissions. The ‘security check’ or ‘background check’ definition should be broadened to include a full range of options and standards reflecting public submissions and comments relating to trusted insider security checks. Other background checks exist – for example they are found in ISO27001, AS4811, the PSPF12, State-based protective security principles, AGSVA’s Baseline, NV1, NV2 & PV offerings and other exempt Agencies security clearances. They seem to have been either ignored or not included.

Submissions to the Consultation Paper

In response to the Consultation Paper, the Department of Home Affairs received 194 submissions. 66 submissions remain confidential and are not publicly available. 128 public submissions are available here. 60 (47%) made comments relating to personnel security. We submitted some observations here & here . Below are all 58 excerpts (left column) with their source link and the right hand side is our commentary.

The Northrop Grumman submission is worth highlighting here:

Government represents a large element of Australia’s critical infrastructure and must be an exemplar. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) and the related Information Security Manual (ISM) sets out the requirements for protective security to ensure the secure continuous delivery of government business. The PSPF and ISM also apply to industry providing goods and services for government departments and agencies. If the PSPF and ISM represent Government’s best practice then it should be used to provide guidance for CI [Critical Infrastructure].

| SUBMISSION | CLVA PERSEC Feedback | |

| 1 | The Federal Government should partially or fully subsidise the cost of ISO/IEC 27000:2018 certification for regulated entities to ensure that those organisations are employing best practice information security management practices and techniques in their day-to-day business.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-031-ISC2.PDF |

ISO27001:A.7.1.1.e is overly vague and only suggests that ‘other checks [should be done] as appropriate’ which is in the realm of a security check. A PSPF12 security check may only cost $135 which is not excessive for the employer to bear and still holds to a ‘user-pay’ model. |

| 2 | —–2—–

The paradox of threat landscape is that one of the only aspects that remains consistent, is that it is continually evolving. Each owner and controller of a Critical Infrastructure asset should be expected to understand the unfolding threat environment as it relates to their specific asset. To accomplish this, effective programmes should include a continuous review of the tools, techniques and actors that are relevant to their systems and assets. Sectorial (industry specific) threat intelligence sharing. Regardless of whether the responsible regulator establishes sectorial SOCs, sectorial threat intelligence sharing will be fundamental to effective incident response and broader cyber resilience. We recommend the regulator mandate owners and operators of Critical infrastructure participate in sectorial threat intelligence sharing. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-138-Active-Cyber-Defence-Alliance.PDF

|

——2—–

Ongoing suitability (PSF13) of actors (personnel) allows for an intelligence sharing mechanism with proper and lawful consent is a good proposal.

PSPF13 & PSPF 14 discusses the passing on of security concerns (and pre-employment info) from one sponsor(employer) to another.

If there was a CIC licencing scheme for vetting agencies (or private public partnership) that could echo the same, it would be a helpful way to participate in insider threat sharing intelligence, as the worker moves from one place to another. |

| 3 | —–3—–

It would be a great initiative for Home Affairs to consider sharing of information between Vetting agencies to provide security clearances that are recognised across all sectors (Police Checks, ASICs, National Security Clearances, Working with vulnerable people etc.) This would standardise requirements for critical infrastructure entities and reduce amount of personal information kept on individuals, (reduction of risk from personal/privacy breach) but also support staff moving between entities.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-178-Airservices-Australia.PDF

|

—–3—–

Sharing intelligence mechanism and standardised requirements are important. The ISM Protect Principle 10 ‘trusted & vetted’ is key and the PSPF12 provides vetting practice standardisation. PSPF 13 & PSF14 offers transferability.

|

| 4 | —–4—–

The AusCheck scheme could be both useful and burdensome. The scheme is helpful to mitigate insider risk as the checking system not only verifies the suitability of an employee to access critical infrastructure, but also puts that person who has satisfied the security checks on alert. The practical difficulty with this, however, is that employees who are subject to the screening process might submit an excessive number of documents to ASIO and the police, and this may prolong the verification process. There is also the question of who should participate in the AusCheck scheme. One suggestion is to impose the requirement on all staff who are authorised to operate critical infrastructure. Another, the preferred choice, is that owners and operators nominate one single employee to undergo the security checks. The SOCI Act may subject this person to legal responsibility should insider risk materialise.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-054-Australian-National-University-College-of-Law.PDF

|

—–4—–

AusCheck could be a prolonged process, if it had to process significantly larger volumes of applications.

All staff to go through vs one representative to go through is interesting and echoes the BEAR – banking requirements. However this contravenes PSPF12 that states all personnel and contractors need to be found suitable.

Although AusCheck liaises with Police agencies and ASIO, it does not check the full number of factor areas that a PSPF background check requires.

If a CI vetting scheme or CI-licenced agency arrangement offered CI sectors affordable risk assessments, overlaid inside their internal recruitment processes, with a service level agreement of 95% done with 5 days, then the PSP12 suitability security check is resolved in a non-protracted manner.

|

| 5 | —–5—–

Over the last 2 years we have been assessing the maturity of our critical infrastructure protections against the proposed Australian Energy Sector Cyber Security Framework (AESCSF). https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-134-Ausgrid.PDF

|

—–5—–

The AESCSF did not recognise AS4811 employment screening as a guiding standard, nor the PSPF12 for suitability screening in Australia. Therefore vetting practices runs the risk of being deficient. |

| 6 | —–6—–

The broadening of the AusCheck scheme (or similar) should only be considered through a riskbased approach on sector by sector basis, with clear linkages to a change in the threat environment for that sector. While the Auscheck scheme is useful for undertaking background checks for new employees, it is significantly limited by the fact it has no on-going monitoring capability for changes in criminal records to notify the employer. This is currently an issue for ASICs in aviation and MSIC in maritime. The costs for industry associated with these schemes are also significant. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-184-Australasian-Railway-Association.PDF

|

—–6—–

By considering a CI-licencing arrangement, or a Public-Private Partnership, initial PSPF 12 (suitability) and ongoing monitoring PSPF13 (ongoing suitability) can be addressed.

There are measures and technology afoot to allow for continuous vetting. The PSPF offers four levels of vetting practice which offers the risk-based approach.

|

| 7 | —–7—–

Airports have expressed to the AAA their concerns that any new Cl regulatory framework is extremely likely to duplicate existing security measures and systems, potentially creating conflicting regulatory regime for airports between physical, personnel and cyber security. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-190-Australian-Airports-Association.PDF

|

—–7—–

Duplication may need to occur, but limiting them to AGSVA, AusCheck and a PSPF-approved security screener provides a way forward. It does not dismantle one scheme but enhances & standardises the CI sector’s screening regimes, especially of personnel those on the CI cusp, including supply chain hazards. |

| 8 | —–8—–

Under the banking sector accountability regime (BEAR), a bank is required to register executives who have accountability for specified areas. These include overall risk controls and risk management, and information management including information technology systems. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-043-Australian-Banking-Association.PDF

|

—–8—–

BEAR appoints leader/s to be vetted, on behalf on the entity (equivalent perhaps of Chief Security Officer – PSPF2, Governance). However, PSPF12 states that all personnel including contractors must be screened for suitability.

|

| 9 |

—–9—– The ACMA notes that there appears to be overlap between the Positive Security Obligation as described in the paper and the requirement introduced into Part 14 of the Telecommunications Act by the Telecommunications Sector Security Reform (TSSR) reforms to protect networks and facilities from unauthorised access and interference. The ACMA encourages further consideration in the design of the Positive Security Obligation to avoid regulatory duplication and provide a clear set of obligations for industry operators.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-021-ACMA.PDF

|

—–9—–

TSSR discusses the difficulty of vetting overseas workers. Therefore an Australian-based screening scheme needs to be able to accommodate such diversity in the workforce to be and not just recognise other private company practices that only screen to a local standard, without consequence of consideration towards Australian security features. |

| 10 | —–10—–

The AESCSF covers a range of domains including three of the four Positive Security Obligation areas – cyber, personnel and supply chain. Extending the AESCSF domains to incorporate physical security [not personnel] should be considered and advanced. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-093-AEMO.PDF

|

—–10—–

The AEMO did not consider PERSEC be considered or advanced to the standard of AS, ISO or the PSPF. |

| 11 | —–11—–

There are over 180 member companies, subsidiaries and associates who together comprise 80 per cent of the gross dollar value of the processed food, beverage and grocery products sectors. The diverse and sustainable industry is made up of over 36,086 businesses. The food and grocery manufacturing sector employs more than 324,450 Australians, representing almost 40 per cent of total manufacturing employment in Australia. AFGC recommends: new regulations imposing Positive Security Obligations on entities responsible for critical infrastructure does not extend to the food and grocery manufacture and supply sector. It is possible that there would be value in extending [AusCheck’s ] coverage to the food and grocery supply sector.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-118-Australian-Food-and-Grocery-Council.PDF

|

—–11—–

Incorporating 324,450 people into AusCheck’s scheme would no doubt overload its capacity. AGSVA has a portfolio of around 400,000 active clearances. However the governance, maintenance and ongoing (PSPF13) suitability regime is outsourced to the Chief Security Officer, Security Advisor and the Security Officer. In more recent times, private businesses (eg DISP members) are becoming responsible for this security element. If 36,086 businesses needed to create new security teams (PSPF2), the AusCheck check scheme is only the tip of iceberg of security compliance. |

| 12 | —–12—–

Adoption of ISO270001 and the maturity model under AEMO’s AESCSF would be appropriate. Consideration of the ASCS role as an intermediary to mitigate supply chain risks, ensuring there is proper segregation, controls, testing and auditing in place end-to-end.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-029-Australian-Gas-Infrastructure-Group.PDF

|

—–12—–

ISO27001.A.7.1.1 Employment screening is overly vague and does not provide a standardised risk management regime nor adjudication guidance to assist decision making processes and protocols. |

| 13 | —–13—–

With respect to the DISP, this is a membership-based program for the defence industry that includes requiring its members to comply with Defence’s protective security policies, practices and procedures. DISP membership is encouraged, and in some cases, it is mandatory to join the program if businesses are doing sensitive or classified work. However, not every business has to have DISP membership to work in Defence. Nevertheless, any business that works in Defence and with industry should have appropriate security protections in place. We would also propose that any compliance costs created by new regulatory obligations should be fully funded/compensated by the regulator as it is done for national interest and security reasons and creates a regulatory burden on business. This will ensure that Government properly implements in practice its deregulation/red tape reduction policy agenda.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-025-Ai-Group.PDF

|

—–13—–

Fully funding a DISP-like scheme would not be practical. Security Clearances, WWCC and AusCheck cards use the user-pay model and it would be difficult to envisage government paying not only for the Initial check itself (PSPF12), but the underlying compliance regime/program (eg. PSPF 2 and PSPF5 reporting, PSPF 13 ongoing suitability) that underpins the organisation’s security posture, which falls into the responsibility of the sponsoring entity. |

| 14 |

—–14—– It is also critical for the Government to fully recognise that regulated security standards and obligations are already imposed on AIP member companies. AIP member companies consider that duplication of existing regulated requirements should be strongly avoided under the Enhanced Framework, as the Consultation Paper commits to. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-101-Australian-Institute-of-Petroleum.PDF

|

—–14—–

By nominating ASGVA, AusCheck and licenced PSPF-vetting companies to conduct vetting work mean that duplication will be reduced, transferability is increased and CI security is managed appropriately. |

| 15 | —–15—–

APPEAs view, if cyber security is to be extended to oil and gas facilities, NOPSEMA should be the Agency through which oil and gas companies continue to interact. This would assist in streamlining and reducing duplication of reporting requirements.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-042-Australian-Petroleum-Production-and-Exploration-Association.PDF

|

—–15—–

NOPSEMA maybe stating that it would like to become the equivalent of the Defence Industry / DISP facilitator – ensuring PSPF compliance (eg. Governance (PSPF 2), Reporting (PSPF5) and so on is carried out appropriately. This sector-specific governance model needs to be considered. Are there other entities that should be participating in this way? |

| 16 | —–16—–

Given the size of these customers, they are capable of managing reliability and security of supply issues and confidentiality matters that meet their requirements through binding contractual agreements with the owners of gas transmission infrastructure. Compliance with such obligations in itself necessitates having appropriate cyber, physical, personnel and supply chain protections (among other things) in place. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-114-Australian-Pipelines-and-Gas-Association.PDF

|

—–16—–

Existing B2B contractual obligations do not usually link back to national security considerations. It is unlikely that they would be linked to ISO or AS type screening for personnel as they relate to foreign influence, espionage or sabotage. Although the nature (the interconnected supply chain and size) of the businesses help in the maturity, process duplication would still exist as personnel move around and the information sharing of insider threats which many are looking for would not be possible through B2B agreements. |

| 17 | —–17—–

There are significant overlaps with the Foreign Interference (FI) and Defence Industry Security Program (DISP) certification requirements. These overlaps include the need for enhanced governance, personnel, cyber and physical security; and to declare foreign interest and ownership issues (e.g. DISP AE250-1 Foreign Ownership & Control Information (FOCI) form). Alignment of critical infrastructure, foreign interference and DISP regulations and guidelines is critical in creating a resilient, effective and manageable university ecosystem. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-129-Australian-Technology-Network-of-Universities.PDF

|

—–17—–

Alignment of critical infrastructure, foreign interference and sector agreed upon regulations and guidelines is important.

Universities maybe able lean into DISP to satisfy this alignment as their projects overlap with Defence-related implications (which are broad).

DISP at the moment is focused, restricted and narrowed to Defence-specific supply chains that impact Defence-contracts. There are many examples of non-Defence national security, foreign interference and influence scenarios that include non-Defence-related projects.

In terms of PERSEC, DISP has AGSVA to carry out PSPF12. Civil Aviation elements do not require AGSVA clearances.

Defence Industry has DISP. Education sector intersect with Defence often. Other CI sectors may need a peak body/authority/Ministers to step up and consider its own DISP-like scheme.

|

| 18 | —–18—–

It is reasonable that Government could expect industry to comply with “best practice” international standards such as ISO 27001 Information Security Management at industry’s cost. However, should the Government require a higher standard or impose additional reporting requirements, BAI believes that Government should pay for any uplift over and above an internationally recognised, standards-based approach. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-022-BAI-Communications.PDF

|

—–18—– The PSPF is a better/higher standard than the existing AS4811 and ISO27001, as it relates to employment screening. There is no national security-related screening guidelines in the ISO or AS. There are no adjudicative guidelines to assist with a determination. There is no professional structured judgement that is required. There is no whole-of-person protocol that is required. AS does not even require a police check. So to ask the government to pay for a police check does not seem reasonable. There are PSPF-12 compliance employment screening services that provide businesses with this security check within three days and less than $150.

|

| 19 | —–19—–

BSA is not able to assess the efficacy or overhead involved in participating in the AusCheck system and whether it could continue to operate through such a large increase in load. Centralised personnel clearance programs are one way to reduce risk but are not the only effective control. They can have issues with poor resourcing impacting throughput slowing recruitment and causing widespread personnel shortages. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-149-BSA-The-Software-Alliance.PDF

|

—–19—–

Another way is a de-centralised personnel clearance scheme. Adherence to the PSPF standard and vetting guidelines should be considered as an effective control. It allows for (a) national security implications and insider threats to be considered appropriately, (b) informational sharing to occur laterally and vertically (c) companies can choose their own providers, (d) costs are competitive (e) the clearance can be recognised and transferred (f) duplication is reduced (g) processing times are competitive (h) third party auditors ensure that the standards and process are met (i) innovation is encouraged – eg. Blockchain, AI etc. |

| 20 | —–20—–

The proposed reforms expands the risks being managed from ‘national security’ (espionage, sabotage, coercion) to ‘all hazards’. Further, it is likely the oversight of security regulation may constitute a new function and area of expertise for some regulators. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-159-BCA.PDF

|

—–20—–

Since April 2019, DISP has opened up a way for businesses to manage counterespionage and security regulations at the company specific level. Defence have a long history in national security and 80% of all security clearances are Defence-related. It will take regulators a herculean effort to stand up a similar DISP program. |

| 21 | —–21—–

The breadth of higher education and research means that a single model is impractical. Research in scram jets or quantum computing needs different controls to English literature. The use of schemes such as DISP in other key research areas is one way forward. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-140-Council-of-Australasian-University-Directors-of-Information-Technology.PDF

|

—–21—–

DISP-styled scheme directed to private companies (eg compliance & reviewing the 750 ISM ‘must’ control measures and 750 ‘should’ control measures etc) is a significant body of work to administer. Would it be a Home Affairs Industry Security Program (HAISP) or a Critical Infrastructure Centre Industry Security Program (CICISP) program, or a Sector Specific-Regulator function. What predicates will be involved for the company to be determined that membership is a requirement or a voluntary? Will all hazards be in play? Will the program outsourced PERSEC to others (eg DISP – AGSVA) and/or AusCheck or an approved panel of decentralised civilian agencies? |

| 22 |

—–22—– A number of the prudential standards also impose personal liability on key personnel within the ADI organisations, ensuring that accountability and responsibility is upheld by the respective businesses. APRA’s existing regulatory framework covering cyber risk is rigorous, sophisticated and operating effectively for the banking and financial services sector. Under BEAR, an individual is identified as an “accountable person” where serving as a member of the board of the ADI or holding senior executive responsibility for one of the listed particular. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-113-Customer-Owned-Banking-Association.PDF

|

—–22—–

Do the prudential standards include national security screening?

Do they meet a side-by-side likeness of a national security clearance, detailed in the PSPF12?

The regular may need to review and enhance the rigour associated to harmonise the BEAR with the CIC/PSPF standards.

Also, BEAR only vets key a small number of responsible executives, while all users of the system would benefit from a fast, affordable, rigorous security background check. |

| 23 | —–23—–

We need to be careful not to over-clear people to keep costs and time delays within reasonable bounds. We also need to acknowledge that vetting agencies are not funded or staffed to deal with mass increase in number. Conversely, at present the AusCheck scheme is a point in time check with little or no capacity for follow-up or on-going checks. Any enhanced personnel security program that emerges from Positive Security Obligation needs to have national application and work across all critical infrastructure sectors to permit individuals to move seamlessly between the sectors without the need to establish their credentials or bona-fides from scratch. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-009-CyberOps.PDF

|

—–23—–

ANAO noted in 2018 that the average 1:500 complex AGSVA NV1 clearance took 640 days.

Fast (eg. AI-enabled), affordable, ongoing and transferable PERSEC can be achieved through a decentralisation approach where government encourages, recognises and approves the use of civilian PSPF-compliant vetting agencies to |

| 24 | —–24—–

Background checks as conducted through AusCheck as well as the ASIO approach for mitigating the risk of insider threats is limited to insider (within boundary) threats. A policies-based framework will be a beneficial reference for the industry and would also provide the sector with guidance on how a national-level security assessment can help leverage existing security controls to better safeguard critical infrastructures against the ever-evolving threat landscape. A consistent approach across all sectors in terms of reference Government frameworks for risk management would be a good way. forward. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-055-Deakin-University.PDF

|

—–24—–

Significant proportions of the Critical Infrastructure sector workforce live outside of Australia and have never has set foot in Australia. This is the problem that AusCheck, AGSVA et al cannot overcome in their present form, as they rely on identification and eligibility of an application to reside in Australia. When they don’t have an Australian address to verify they will fail the first step.

Having Australian vetting officers consider foreign applicants in terms of foreign influence, association and loyalty is a missing piece in the counter-espionage landscape at this point.

Any national level security assessment needs to consider suitability from an Australian sovereignty perspective and needs to encompass (not disqualify) non-Australian residents for the process. Allowing concessions in these situations, an innovative civilian suitability vetting agency could tailor an appropriate assessment, while offering a consistent approach across all sectors. |

| 25 | —–25—–

Energy Industry uses several International Standards or Australian Standards such as o Asset Management is ISO 55001; o Health and Environmental Safety ISO 14001; o Risk Management ISO 31000; or o Information Security ISO 27001, ISO 27002 and ISO 27019, It is essential to ensure that security standards align to already existing International or Australian Standards to ensure easy adoption and alignment with existing practices. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-156-Endeavour-Energy.PDF

|

—–25—– The ISO 27001 does not focus of personnel screening, but in ISO 27001.A.7.1.1 lists a few items that should be contained in the security check Existing International and Australian Standards do not provide adjudication guidelines, nor any specificity in terms of Critical Infrastructure national security screening, such as foreign influence, coercion and loyalty.

The uplift of IS & AS standards that includes the PSPF should be considered a better way forward.

Easy adoption through a fast, affordable PERSEC security check inside the recruitment process and existing practices will reduce the burden of adoption.

|

| 26 | —–26—–

A small number of critical roles may benefit from additional background checks and information sharing similar to the sectors in the AusCheck scheme.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-060-Essential-Energy.PDF

|

—–26—–

IBM stated that 20% of data breaches happen due to accidents. 40% of all incidents are due to malicious trusted insiders. Limiting a security background screen to just those with ‘critical roles’ will reduce the efficacy of the vetting regime and will reduce the cyber awareness relevance and the security culture in the workplace. Consistently checking for foreign influence, counter-productive workplace behaviours and data breach violations should be considered a minimum for all staff and contractors working on Critical Infrastructure.

|

| —–27—–

Implementation of the PSO in the STN – entities within the STN are subject to multiple layers of governance, including GNGB’s own governance framework and the ATO’s Operational Framework. Entities providing services to super funds are also subject to the requirements of CPS234 as they relate to third parties.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-065-Gateway-Network-Governance-Body.PDF

|

—–27—–

CPG 234.7.a states that typically an ADI undertakes due diligence processes before granting access to personnel. The use of contractors and temporary staffing arrangements may elevate the risk for certain roles.

The uplift of this due diligence that meets PSPF12 is consistent with the submission: it does not duplicate processes, nor does it add additional layers of governance.

|

|

| 28 | —–28—–

New University Foreign Interference Taskforce. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-083-Griffith-University.PDF

|

—–28—–

Extending suitability assessments to student applications who have applied for sensitive national security-related courses should also be considered. Mechanisms already exists to review and exclude unsuitability students, however, by placing more rigour around foreign government influenced students would also assist to strengthen counter-espionage activities. |

| 29 | —–29—–

In the briefing, the Home Affairs staff repeatedly drew attention and emphasis to the notion that this risk management extended to University personnel. What exactly is meant by these risks? Existing measures are: • the continuing work of the University Foreign Interference Taskforce, and the Guidelines to counter foreign interference in the Australian university sector • the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act 2018 • the proposed Inquiry by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security into foreign interference in Australian universities https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-078-Group-of-Eight.PDF

|

—–29

What exactly is meant by these risks? The PSPF Adjudicative Guidelines quote: If/when a person acts in ways that indicate a preference for a foreign country over Australia, then they may be prone to act in ways that are harmful to the national interest of Australia. A security risk may exist when they or their immediate family are not Australian citizens or may be subject to duress. These situations could potentially introduce foreign influence that could result in the compromise of security classified information. Contacts with citizens of other countries or financial interests in other countries are relevant to security determinations if they make the clearance subject potentially vulnerable to coercion, exploitation or pressure. |

| 30 | —–30—–

Strengthening Public-Private Partnerships. ITI supports continued strengthening of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and bolstering information sharing among industry and government in order to appropriately assess threats and prevent incidents. International Standards. We recommend that Australia’s policies continue to support and utilize globally recognized and state-of-art approaches to risk management, such as the ISO/IEC 27000 family of information security management systems standards. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-063-Information-Technology-Industry-Council.PDF

|

—–30—–

Other than AGSVA, there is little (if any) information sharing among industry and government concerning trusted insiders that appropriately assesses insider threats and help to prevent incidents. Having authorised PSPF-compliant civilian suitability vetting agencies assessing and protecting critical infrastructure from security incidents, sabotage, espionage and foreign influence should be welcomed and encouraged. |

| 31 | —–31—–

Models to Mitigate the Risk of Insider Threats. Given the national importance of the data and systems, CI employees, contractors and service providers should undergo stringent vetting processes in alignment with the Protective Security Policy Framework and Australian Government Security Vetting Agency clearances. These processes have ensured that Service Providers are able to provide critical services to Commonwealth entities, including access to and sharing of information at protected level, which is paramount to the successful provision of cybersecurity services.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-085-Leidos-Australia.PDF

|

—–31—–

We couldn’t agree more with Leidos’s view. Aligning and recognising the stringent vetting practices detailed in the PSPF vetting practices conducted either by AGSVA or by approved third parties will allow the right people to have access to the right information at the right time. |

| 32 | —–32—–

The Medical Software Industry Association Ltd (MSIA) represents the interests of health software companies which power better outcomes for all Australians. The use of existing registries in health may be more appropriate e.g. AHPRA Services Australia modernisation programme will be leveraging off work done with the Digital Transformation Agency, ADHA and others on credentialing like PRODA etc. Not all industries have the same requirements e.g. Blue Card is not essential for Residential Aged Care Workers but critical in educational facilities. Even the ISM is not broadly accepted as being the optimal solution for health. This requires further consultation. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-120-Medical-Software-Industry-Association.PDF

|

—–32—–

The ISM P10 refers to only‘ trusted and vetted personnel’ accessing systems. ISM security control 0434 ‘appropriate employment screening’ should be ‘broadly accepted as being the optimal solution’ for health. Aged Care will have their own clearance process with an industry code of conduct blacklist on their centralised screening scheme. Education vetting has something similar. Having an information sharing agency has benefits as they relate to Critical Infrastructure. |

| 33 | —–33—–

Align Australian regulatory requirements with international standards and best practices based on cross-sectoral baselines. Both the ISM and the APRA guidelines provide good risk-based frameworks https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-111-Microsoft-Australia.PDF

|

—–33—–

ICAC NSW says that better practices are found in PSPF 12, partially because the PSPF provides adjudication guidelines and a non-discriminatory, whole of person, professional structured judgement. The ISM P10 ‘trusted and vetted’ is a good framework. |

| 34 | —–34—–

Government represents a large element of Australia’s critical infrastructure and must be an exemplar. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) and the related Information Security Manual (ISM) sets out the requirements for protective security to ensure the secure continuous delivery of government business. The PSPF and ISM also apply to industry providing goods and services for government departments and agencies. If the PSPF and ISM represent Government’s best practice then it should be used to provide guidance for CI. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-109-Northrop-Grumman-Australia.PDF

|

—–34—–

The PSPF does represent Government’s best practice and should be used in personnel security checks (PSPF 12, 13, 14) within the Critical Infrastructure context. It is unreasonable to conclude (and the exact opposite of this submission posture) that only government departments can deliver PSPF-compliant vetting. Any CI personnel security scheme should be PSPF-compliant and cover the 7 factors areas and 21 security concerns evaluated by vetting agencies (which is, at present, beyond the scope of AusCheck). |

| 35 | —–35—–

Critical infrastructure networks are more vulnerable to cyber threats due to their nature in providing services to the citizen and are not seen as being within a secure perimeter. Beyond agreed vulnerability scanning and penetration testing, personnel and physical security should also be tested. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-077-Oceania-Cyber-Security-Centre.PDF

|

—–35—–

Testing personnel for honesty, trustworthiness, tolerance, maturity, loyalty and resilience (HTTMLR) is defined in the PSPF. These tests have occurred more than 400,000 times via the AGSVA clearance process. To be able to open this up to more sectors, include CI, would make a significant contribution. |

| 36 | —–36—–

Extend the requirement for MSIC and security checks to all maritime employees, and not just those that work on the waterside zones. Insider threat is considered high risk now. There may need to be other background checks for IT personal working in critical infrastructure cyber security and also support staff working on Critical Systems within entities. Additional costs associated with increased security clearances will be passed on by PBPL to end users / customers and we anticipate any vendors required to comply with this will also pass on costs. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-005-Port-of-Brisbane.PDF

|

—–36—–

Extending security checks (be it AusCheck or another similar CI-related PERSEC scheme) to even more people who are working in critical infrastructure contexts – including support services, such as IT – allows for the vetting standard to be consistently and fairly applied. |

| 37 | —–37—–

The VPDSS establishes 12 high level mandatory requirements to protect public sector information across each of the security domains (i.e. governance, information, personnel, information communications technology (cyber) and physical security). The VPDSS reflects national and international best practice approaches towards security, tailored to the Victorian Government environment. Existing Commonwealth frameworks. OVIC also queries the need for an enhanced regulatory framework in light of existing national mechanisms such as the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) and Information Security Manual (ISM), schemes in which the Commonwealth Government has already heavily invested. The Victorian model was developed to closely align with international and national security frameworks and standards, complementing the requirements and controls set out at the Commonwealth level under the PSPF and ISM. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-040-Office-of-the-Victorian-Information-Commissioner.PDF

|

—–37—–

Claims of alignment with frameworks may be vulnerable to weakness and fragility and if applied to CI, the risks are too high to be complacent. Who audits the proximity of alignment? Does close alignment mean drug use is checked & how, or are regular foreign contacts are investigated and if/when referred onto ASIO? What does ‘complementing the requirements’ actually mean? Example: The Victorian Auditor General noted that 60% of contractors (more than 3,400) working in the Victorian Public Service did not have a criminal history record check. It is hard to believe that PSPF adjudicative policy, procedural fairness process, the application of a whole-of-person principal within a professional structed judgement (all specifically highlighted in the PSPF) is being done all the time, every time, as per ASGVA. |

| 38 | —–38—–

Maritime Security Identification Cards are provided through the AusCheck scheme are perceived to be sufficient in its risk mitigation of insider threats. For other port workers, there are differing requirements. Cargo terminal operators, which enter general port areas and do not enter a maritime security zone are controlled under and need to satisfy requirements within the Customs Act 1901 and associated regulation. It is suggested that assessment criteria for sectors is aligned where possible. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-185-Ports-Australia.PDF

|

—–38—–

1 in 10 AusCheck holders have serious criminal histories. 277 AusCheck holders were on criminal or gang-related or terrorist watch lists, yet still able to hold the card. It should be noted that the AusCheck ASIO Assessment is vastly different than the NV1 AGSVA ASIO Assessment. An AGSVA Baseline does not include a ASIO assessment as a standard. |

| 39 |

—–39—– The Australian Energy Market Operator’s Australian Energy Sector Cyber Security Framework (AESCSF). The core framework is mapped to National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF), and Electricity Subsector Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (ES-C2M2), and cross references the relevant global and Australian Cybersecurity best practices and standards e.g. Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) Essential 8 and ISM, Australian Privacy Principles, ISO27001, etc. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-059-Powercor-CitiPower-United-Energy-SA-Power-Networks.PDF

|

—–39—–

The ISO 27001 employment screening (A.7.1.1) is overly broad. It does not clearly require a ‘security check’ for CI sectors. The ISO is not designed to provide a method or guidance as to make decisions, only that the ‘CV should be checked, Police check should be done’ etc. As noted by one submitter, E8 has not been achieved by 29% of commonwealth departments, even after they were victims of high-profile cyber-attacks.

|

| 40 | —–40—–

Dynamic threats combined with the fragmented nature of critical infrastructure operators both locally and internationally, means the problem can only be tackled in an holistic multi-disciplinary fashion. Cyber, physical, personnel and supply chain risks will only continue to converge. PwC believes the objective for the Government should be to support the establishment of cyber ‘situational awareness’ – in the form of technology, people and processes – across multiple critical infrastructure sectors, in collaboration with industry regulators, specialist vendors and critical infrastructure operators. In this context, ‘situational awareness’ refers to our ability as a nation, to maintain an up-to-date and holistic view of the cyber security threat and vulnerability landscape across critical infrastructure. We believe technology can play a key role in enabling the consultation, adoption and ongoing maintenance of critical infrastructure security reforms.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-150-PricewaterhouseCoopers.PDF

|

—–40—–

The converging nature of these risks requires situational awareness which includes using specialist vendors who have assessed trusted insiders (PSPF12) and can offer up-to-date, real time, ongoing maintenance (PSPF13) of personnel security to support vulnerability assessments and incident management and intelligence sharing as required.

|

| 41 | —–41—–

Under the Operating Requirements to which ELNOs are subject, good corporate character and reputation requirements extend to the taking of reasonable steps to ensure that employees, agents and contractors are not and have not been subject to various matters. These include insolvency events, convictions for fraud and other offences in connection with business and commercial activities and other professional disciplinary events. Given the increasing threat environment that many operators of critical infrastructure face, the AusCheck scheme or a similar model would be useful in ensuring a more comprehensive set of checks are carried out to address insider threats. We are unaware as to whether the operators of other critical systems in our sector, including land registries, are subject to similar character check obligations. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-107-Property-Exchange-Australia.PDF

|

—–41—–

AusCheck does not review alcohol & drug use, finances, security violations, personal conduct or mental health factor areas. AuCheck limits its scope to allegiance (ASIO check) and criminal history. Therefore a ‘similar’ model would be useful in ensuring a more comprehensive set of checks are carried out to address insider threats. Character check obligations are detailed and defined in the PSPF as Honesty, Trustworthiness, Tolerance, Maturity, Loyalty and Resilience (HTTMLR) and assessed in four risk levels. |

| 42 | —–42—–

Key road and rail mass passenger transport services are currently declared as security identified surface transport operations (SISTOs) under the Transport Security (Counter Terrorism) Act 2008 (Qld) and as such, already have physical and personnel security arrangements in place. Investment by entities in the development of a security culture may be a more important mitigation factor which should be encouraged. While a useful starting point, national security and criminal history assessments are a point in time assessments which may only add limited value. The first Australian ever convicted of a terrorism offence (in Lebanon) held an Australian Aviation Security Identification Card. Any additional requirements on businesses for security checks would need to be adequately supported (resourced) by vetting agencies to minimise disruption to business due to lengthy delays in processing applications. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-191-Queensland-Department-of-the-Premier-and-Cabinet.PDF

|

—–42—– The Transport Security (Counter Terrorism) Act 2008 (Qld) does not prescribe personnel security arrangements so we are unsure to which standard they are working to. It is true that national security and criminal history assessments (PSPF12) are at this stage point-in-time assessments, continuous vetting is coming and when combined with employer-led (ongoing suitability) PSPF13 a security culture and practices are upheld. For example, DISP Members who need to maintain security clearances, have around 15 touchpoint obligations per year: ranging from induction, training, awareness, briefings and reporting obligations with security-related obligations. Any initial or additional security checks are just the tip of the iceberg, the employer-led security regime must be adequately supported and resourced. |

| 43 | —–43—–

It is important to specify the framework that would be used by the regulators to assess industry compliance. It is recommended that existing security and audit certifications and frameworks such as the IRAP, ISO 27001, ISO 27017, ISO 27018, SOC should be relied upon.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-056-Salesforce.PDF

|

—–43—–

ISO27001.A.7.1.1 is overly general as it relates to personnel security and the PSPF has been seen as the framework of choice. |

| 44 | —–44—–

A similar scheme [to AusCheck] would partially address the risk of insider threats from a human perspective within a specific sector. However, it would not account for human based insider risks within critical infrastructure associated supply chains.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-174-Sapien-Cyber.PDF

|

—–44—–

A CIC-sponsored or endorsed civilian vetting scheme would deter and detect insider threats. Any supply chain (eg. DISP) personnel that interacts with or has access to Prime’s assets, resources or personnel should be be screened and verified as part of the vendor management system and information sharing protocols to confirm the end user’s, or visitor’s suitability to have access. |

| 45 | —–45—–

Many of the security considerations outlined in the consultation paper are already covered extensively under procedures and regulations currently in place. These include but are not limited to Protocols and relationships developed through the University Foreign Interference Taskforce; and Reporting requirements under the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012. We do not see any clear evidence to suggest Australian universities and research institutions such as medical research institutes need further regulation beyond the already strong systems in place. University Foreign Interference Taskforce. The security of our national infrastructure is not a static challenge. It is the subject of ongoing adaptation as new threats and risks emerge. It is in the spirit of this evolving landscape that the University Foreign Interference Taskforce was formed last year as an equal partnership between the university sector and agencies of Government. This taskforce includes representatives of the university sector and representatives of Australian Government Departments including Home Affairs, Education, Attorney-General’s, Defence, and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. Our of the work program of four specialist working groups that fed into the taskforce, a set of guidelines and best practice principles were developed and released in 2019 to assure the security of Australia’s research and research infrastructure. The Guidelines to Counter Foreign Interference in the Australian University Sector were designed to enable ongoing consultation and updates of shared security practice in a more flexible and nimble approach than heavy-handed red tape or regulation. Such an approach means universities can regularly address new risks to their systems and research infrastructure based on rapid advice from taskforce members based in national security agencies. STA sees this taskforce as a more effective protective measure than additional legislation that will increase regulatory burden without the rapid response and mutual partnership approach that this taskforce has established. This is not to say sensible and proportionate risk management is not needed, but rather that regulation should not seek to double up on work already being undertaken on a voluntary partnership between research institutions such as universities and national security agencies. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-181-Science-%26-Technology-Australia.PDF

|

—–45—–

A shared security practice which is a more flexible and nimble approach should be adopted for all CIC Sectors, in contrast to a heavy-handed red-tape, 4-8 month type clearance (complex cases 640 days for a NV1) that would impede the sectors.

For example a PSPF12 Baseline-equivalent assessment (delivered within 5 days) with a Intelligence Community “rapid advice” service as required would be flexible and nimble.

For example, CI companies share the load by completing the ID requirements (eg. National Proofing guidelines or Digital Verification Service check) reducing duplication and then the authorised civilian vetting agency assesses the suitability based on employer information sharing and its own investigations. |

| 46 | —–46—–

South Australia is enhancing protective measures through the new SAPSF which establishes information, personnel and physical security requirements which each department must apply based on their risk and operating context, which will be supported by a security maturity assessment model that will identify and assure progressive improvements. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-096-SA-Department-of-the-Premier-and-Cabinet.PDF

|

—–46—–

We would hope that the ‘new’ protective personnel security measures includes the full seven factor areas and 21 security concerns detailed in the suitability component of the PSPF12, especially outcome determination mechanisms. |

| 47 | —–47—–

Splunk recognises the importance of criminal and national security checks of staff in relevant security environments. Splunk conducts such checks itself and, to conduct its work with governments and defence forces, has a considerable number of employees with Five Eyes security clearances. While important, such checks offer a snapshot in time of an individual’s potential security risk and may only be conducted once or with years in between. It is also understood that national security assessments are resource and time intensive. Splunk believes that a continuous assessment model which monitors and analyses appropriate data about employees’ at-work behaviour is the most practical way to measure and flag insider threats. A continuous assessment model complements checks by providing longitudinal information on an individual’s insider threat risk profile as their life circumstances change. Insider threat analysis software is widely available and provides an effective, affordable, scalable, time sensitive, and privacy appropriate way for critical infrastructure providers to manage such threats. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-035-Splunk.PDF

|

—–47—– National security assessments pursuant to PSPF12 and delivered by AGSVA are resource and time intensive. Complex NV1 cases can take on average 640 days.

A nimbler way forward needs to be found. PSPF13 describes ongoing suitability elements that the employer needs is responsible to lead with. The employer-led continuous assessment model that monitors users is valid. The DISP program now obliges companies to have more than 15 touchpoints with their personnel for security and cyber training, awareness, training, and reporting. Together it is the most practical way to measure and flag insider threats. |

| 48 |

—–48—– TasNetworks supports personnel security checks for those employees and contractors who have access to assets. We consider the most appropriate standard is Baseline Vetting, as outlined in the Australian Government’s Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF). This provides the most appropriate balance between cost and security control. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-100-TasNetworks.PDF

|

—–48—–

A PSPF-compliant Baseline vetting standard does not need to be delivered by ASGVA. The 6-8 week lead time maybe problematic and $700+. If it was delivered by CIC approved civilian vetting specialist which considers espionage, foreign influence and sabotage, but can compete the PSPF-compliant assessments – even for non-Australian citizens) with 1-3 days, there might be a compelling proposition to consider other schemes. |

| 49 | —–49—–

Telstra routinely conducts background checks when appointing people as employees or engaging them as contractors using a risk-based approach. The background checks undertaken depend on the nature of the role and responsibilities the employee/contractor will undertake and which information, customers and systems they will have access to. We do not believe there is currently a need to introduce AusCheck as an additional assessment over and above Telstra’s existing due diligence. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-143-Telstra.PDF

|

—–49—–

Telstra’s (like many large ASX companies) due diligence may consists outsourcing police checks, ref checks and ID checks to third party vendor. It is doubtful that (other than AGSVA clearances processes) that Telstra’s pre-employment due diligence include counter espionage, foreign influence and sabotage vulnerability assessments that match the CIC national security requirements nor the rigour of the PSPF. |

| 50 | —–50—–

Telstra Health does not use the AUSCHECK program. Rather, we use the DISP system conducted by Defence and as directed by the Department of Health as a requirement for our role in operating the National Cancer Screening Register (NCSR). The NCSR is ISM compliant and governed by the Commonwealth NCSR Act. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-032-Telstra-Health.PDF

|

—–50—–

The DISP Entry level system requires that non-national security cleared personnel be AS4811-2006 employment screened which does not even require as a ‘must’ a Police check. Citing a driver’s licence is basic enough to be considered ‘a trustworthy individual’. |

| 51 | —–51—–

The security clearance requirement should be expanded to everyone providing services to critical infrastructure providers. Introduce a . Using cyber security as an example, two existing industry qualifications such as CISSP and CISA, etc. can be used to formally license cyber security professionals via the Australian Computer Society. This will ensure a common standard is enforced across these providers. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-011-Unisys.PDF

|

—–51—–

Licensing personnel security providers to service critical infrastructure makes sense. Imagine having a choice of vetting agencies: perhaps these entities are owned by a non-profit or membership-based organisations. If a security vetting agency was owned by a non-profit organisation, then it would provide additional assurances to (and potential endorsement by) government. Customers would also feel that profit-incentivisation aspects would be held appropriately in check. For example, a non-profit research company could own thousands of active investigative files and study the longitudinal data to discover new vetting insights and enhance critical path to insider threats models. |

| 52 | —–52—–

At present, there is a lack of clarity on how thresholds or classification of risk would be defined or applied. Whilst there is some clarity on how the legislation would be applied to cybersecurity, there is no clarity on how it might apply to physical infrastructure, personnel and supply chain infrastructure. Avoid duplication of regulation and take a risk-proportionate approach. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-148-Universities-Australia.PDF

|

—–52—–

The PSPF offers four levels of vetting practice which provides clarity of thresholds of risk. By using the PSPF12 and its associated vetting practices and adjudication guidelines, there is no need to adjudicate via legislation (compare AusCheck and its legislative prescription). Also, by information sharing, duplication is also reduced and a risk-proportionate approach is met. |

| 53 | —–53—–

The AusCheck scheme should be implemented for other areas of critical infrastructure (assets of strategic national importance), in particular electricity generation and distribution, major water facilities, and first responders. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-039-University-of-KwaZulu-Natal.PDF

|

—–53—–

AusCheck and AGSVA should be used as ‘last resort’ to limit the demand and workload they would be burdened with. If the private sector can answer these challenges and solve and deliver PSPF-compliant civilian suitability scheme (or a Private-Public Partnership) it can offer CI sectors a viable alternative. |

| 54 | —–54—–

The Victorian Protective Data Security Framework and Standards (VPDSF and VPDSS) that V/Line must comply with as part of the Victorian public sector is the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards – VPDSS and Victorian Protective Data Security Standards – VPDSS: Standard 10 – Personnel Security. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-018-VLine.PDF

|

—–54—–

Which is to say that E10.030 PER-030 states that the organisation must undertake pre-engagement screening commensurate with its security and probity obligations and risk profile. It may or may not include seven factor areas of PSPF12 or for example assess the vulnerability to foreign influence, coercion, espionage. |

| 55 | —–55—–

AusCheck results on individuals may be useful for CI outside of Data and the Cloud, however given the sensitive and critical nature of Data and the Cloud, Australian Government Security Vetting Agency clearances for all staff that work for the Data and the Cloud sector providing services to Government or other CI sectors, should be mandatory at an NV1 level. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-154-Vault-Cloud.PDF

|

—–55—–

The AGSVA has a significant role to play at the NV1 level. However most commercial PROTECTED-level cloud providers mean they only require a BASELINE clearance. Recommending all should be NV1/SECRET holders seems to be over-vetting or over-clearing. A PSPF-compliant BASELINE-equivalent clearance with the ability (reviewing seven factor areas) and as required to conduct an ASIO check means that industry can offer an alternative scheme, with Public partnership and arrangements as/when necessary. |

| 56 | —–56—–

The Victorian Government would not support an AusCheck style scheme for personnel registration and security checks without a clear evidence base outlining the need and a thorough understanding of industry impacts. Instead, Victoria would welcome an approach that looks to identify the most critical and vulnerable roles rather than take a blanket approach to sectors or systems.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-026-Victorian-Government.PDF

|

—–56—–

Australia needs to protect Critical Infrastructure from espionage, sabotage and foreign influence. E10.040 PER-040 notes that its screening process manage ongoing personnel suitability requirements that are commensurate with the risk profile. If the Victoria government’s screening processes meets these new CI security obligations and uplift in risk profile/s, then there would not be a need to duplicate. |

| 57 | —–57—–

Compliance costs. In the absence of details of the proposed regulatory regime, it is difficult to estimate the potential compliance costs for each water business. However, it’s envisaged that additional costs would be incurred in terms of security personnel (in-house or outsourced) along with capital and operational expenditure. Ongoing compliance with the cyber-security element and other elements of the positive security obligations may also result in an increase to annual operating costs. While the imperatives for growth may now be different, the general lessons remain valid and extant. Based on that experience, it is clear that the initial costs of hardening and monitoring of physical assets, vetting and monitoring of personnel, enhancements to the supply chain and upgrades associated with cyber security, along with the cost of audits and compliance, will likely be significant. While ongoing costs will be significant, there is also a history of scope creep and inclining costs until full maturity is reached, noting that this may take 5-10 years. The implementation of such a [AusCheck] scheme would need to be proportionate to the risks. In water, the disaggregated nature of the sector and low number (if any) of Systems of National Significance are indicators that such a measure would not be commensurate to the current level of national risk in relation to the water sector. Noting the application of the Personnel Security principles as part of the Positive Security Obligations will provides direction on appropriate personnel security risk controls including vetting. These would then be operationalised with clear guide on best practice for the sector though the sector regulation. In particular: • The water sector recognises the benefits of AusCheck scheme. • The water sector believes that the application of the scheme should be calibrated to or aligned with the graduated or hierarchical classification scheme • Therefore, the question of whether the water sector should be subject to such a scheme depends upon its eventual classification within that typology. • If the water sector is subject to this scheme, then the question of which roles should require an AusCheck should be matter of negotiation between the sector, the entity and the regulator. • The water sector recognises that there are costs and IR impacts inherent in the AusCheck scheme and that this needs to be weighed against its potential personnel security benefit. The current costs of these impacts are uncertain and requires more detail, particularly in relation to how broad (in terms of coverage) would the model be. Should it be applied to employees, contractors or both, and whether existing controls were sufficient to address the perceived threats? Cyber, Personnel, Physical testing should be carried on a regular basis by the entity and independently on a regular basis. (Pen testing, vulnerability assessments, red teaming, background checking).

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-128-Services-Association-of-Australia-NSW-Water-Directorate-Queensland-Water-Directorate-VicWater-and-the-Water-Services-Sector-Group.PDF

|

—–57—–

If organisations are already meeting ISO or AS employment screening standards, then adding a PSPF12 security screening scheme overlayed on top of (and say inside of the recruitment process) then process is not significantly changed, no capital or operational expenditure is require by the organisation. The AS & ISO are uplifted to satisfy the CI security needs, the cost and time are minimal. We estimate that the initial costs of vetting and monitoring personnel are in the vicinity of $135 per assessment (PSPF12) and $35-$45 per person per month (PSPF13). This is proportionate, fast, affordable.

The question of which roles should require PSPF12 vetting check, an AusCheck or an AGSVA clearance should be matter of negotiation between the sector, the entity and the regulator.

The PSPF12 security check should be applied to both employees and contractors who have access to CI assets, information, systems and personnel. It would be fair to say that existing controls are not sufficient to address the perceived trusted insider threats, unless the organisation already vets for foreign influence, espionage and sabotage and security violations and security breaches.

Personnel testing should be carried on a regular basis by the entity (as per PSPF13) and should be tested (audited) independently on a regular basis – perhaps like the Defence Industry Security Program scheme.

|

| 58 | —–58—–

WTC supports an approach which achieves a baseline of cyber, physical, personnel and supply chain protections based on a framework built around principle-based obligations sitting in legislation. The AusCheck scheme may be beneficial, but any responsible entity does detailed checks on new employees which may be as detailed or more detailed than AusCheck.

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/critical-infrastructure-consultation-submissions/Submission-090-Wilson-Transformer-Company.PDF

|

—–58—–

Submissions have referred to PSPF being the most appropriate framework and it sits within legislation already.

AusCheck does a criminal history check and an ASIO check and uses legislation to deem applicants eligible. Not many responsibly entities routinely do more than that.

The PSPF12 expands the AusCheck background check to include seven factors areas and 21 different security concerns that are investigated (including a one-on-one interview), analysed and adjudicated. |

Conclusion:

There seems to be an opportunity for Australia to deliver an industry-led, innovative, yet standardised background checking scheme that reduces duplication – is nimble, fast, transferable and offers ongoing management and advice. It seems to balance the required uplift of employer’s positive security obligations while meeting government’s all hazard, national security, PERSEC concerns.

We welcome discussion in the co-design sector specific workshops that consider sector-specific requirements, the risk profiles and thresholds. We look forward to discussing existing government schemes (the pros & cons) and also to encourage Industry to look to potential private solutions that meet requirements.

Read more:

Critical Infrastructure Entities Must Now Hunt For Spies.

Introducing Australia’s first CI Clearance.